WORLD WAR II VETERANS CONCORDIA PARISH LOUISIANA

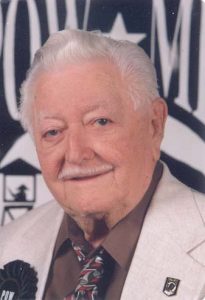

ARMY AIR FORCE LLOYD F. LOVE

EUROPE MAJOR AIR FORCE RESERVE

37th Bomb Squadron, 17th Bomb Group Pilot B-26

Combat Experience————73 Missions over Europe 1/19/44 to 11/4/44

Awards: Air Medal with Eighteen Oak Leaf Clusters

Expert in Aerial Gunnery

I was born July 15, 1921 near Eva Louisiana on Black River on property previously owned by Louis Campbell. I am the son of James Hartwell Love and Sadie White Love. My great grandfather was Louis Campbell who was one thirty-three children of Beasley Campbell.

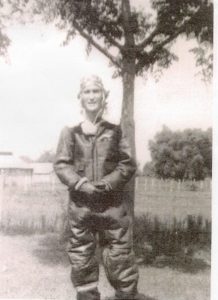

I graduated from Monterey High School in June 1938 and entered LSU in September 1938. While a student at LSU, from 1938 to 1942, I was in the ROTC and was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant in Infantry. I also participated in the CPT (Civilian Pilot Training) program and learned to fly. I was ordered to active duty at Fort Knox, Kentucky in June 1942. Later I transferred to the Army Air Corps and did my pilot training in Texas. I had primary training in Corsicana, Texas and then went to Sherman, Texas for basic training. I graduated, after advanced training at Aloe Field, Victoria, Texas.

I graduated from single engine school in August 1943 and was sent to Barksdale Field, Shreveport, Louisiana where I was assigned to training in the Martin Marauder B-26. This airplane was called “The Widow Maker” and “The Flying Prostitute”, among other things; obviously, a dangerous airplane.

Our crew was sent to Europe in December 1943. We flew from West Palm Beach, Florida to Borinquen Field, Porto Rico, to Atkinson Field, British Guiana, to Belem, Brazil, South America. From there we crossed the Atlantic to Africa with a stop-over at Ascension Island, a rock in the ocean with a 3000 foot runway. Finally we reached Sardinia, a large island in the Mediterranean Sea. There we were assigned to the 37th Bomb Squadron of the 17th Bomb Group.

This was the group, that had previously flown the Tokyo Raid with Colonel Jimmy Doolittle, later to become General Doolittle and command the Eighth Air Force.

We flew tactical missions over Italy and France. Tactical missions were those in direct or advanced support of our ground forces. I flew 73 combat missions. I went on my first combat mission January 19, 1944. We bombed an airdrome in Italy. Other types of targets were viaducts, railroad bridges, support of the Anzio beachhead, railroad marshalling yards, highway bridges, port facilities, gun emplacements and fuel storage. D Day for the invasion of Southern France was August 15, 1944. A bridge was our target that day. Our trip home was in December, docking in New York harbor December 14, 1944.

We had a narrow escape in January right after we got to Sardinia. On take-off the right tire blew out just as we got to 150 miles per hour. The wheel twisted off and came back into the bomb bay. It knocked one of the bombs off so that it was bouncing around. After we skidded to a halt, we discovered that the bombardier had pulled the safety pins while we were on the ground. It was a live bomb. We survived only by the grace of God.

In January 1945 I was sent to Laughlin Field, Del Rio, Texas, where I flew until the war ended. After the war ended, I was sent to Chennault Field, Lake Charles, Louisiana. I had intended to stay in the Army, but in September, I went to Baton Rouge to see an LSU- Alabama football game. That weekend, I met Ann Jackson from Tennessee. I went back to Chennault Field and told the Army that I wanted out of the Army, so that I could go to Law school.

I married Ann Jackson August 31, 1947. And graduated from LSU Law School in May 1948. We moved to Ferriday in September 1948. We have four children; Phyllis, married to Richard Mayo, Louis, a single man; Julie, married to Bernard Cole; and James (Jimbo) a single man. We have four grand children, Jake and Erik Mayo, and Emily and Katie Cole. I have been as active as I could, for the benefit of the community, and have been very active in the Ferriday Rotary Club and the LSU Alumni Foundation.