WORLDWAR II VETERANS CONCORDIA PARISH LOUISIANA

U.S. NAVY W. L. STEWART

Mine Sweeper – USS Garland (AM 238) Yeoman 2nd Class

The USS Garland received 2 Battle Stars for major engagements.

Awards: American Area Campaign Medal

Asiatic Pacific Campaign Medal

World War II Victory Medal

I was born October 1, 1925 at Haynesville, Louisiana and lived at Bossier City, Louisiana until I entered the service January 26, 1944. I was a member of the initial crew when the USS Garland was commissioned in Puget Sound August 26, 1944.

The USS Garland departed San Pedro, California, November 12, 1944 with a convoy to Kossol Roads, Palau Islands, arriving there January 2, 1945, where she served as Entrance Control Ship. The Garland escorted convoys between Peleliu and Ulithi until May 20; then patrolled convoy routes between Ulithi and Eniwetok. She departed Ulithi June 28, escorting a 16 ship convoy to Buckner Bay, Okinawa, arriving there July 17, 1945.

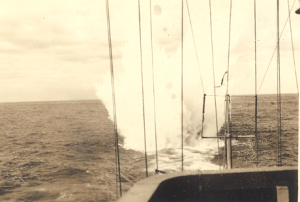

Based at Buckner Bay, the Garland swept mines in the East China Sea July 22 to 31 and August 13 to 25. Next she shifted to Ominato Ko, Honshu, sweeping Japanese mine fields to clear the way for Allied transports, carrying occupation troops to the Empire. The Garland departed Ominato Ko October 20, serving as flagship of Mine Division 40 until November 20. Then she sailed for the United States, arriving at San Diego December 19. Departing San Diego January 31, 1946 and going through the Panama Canal, she went to Orange, Texas where she was decommissioned August 2, 1946.

I was released from service at Orange, Texas June 11, 1946. I moved to Concordia Parish in 1954. August 27, 1971 I married Valerie Finney, whose home was in Catahoula Parish. We now make our home at 143 Chandler Road, Ferriday.

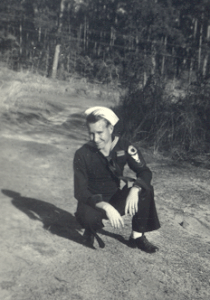

Me as a Sailor

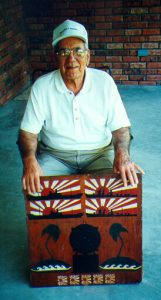

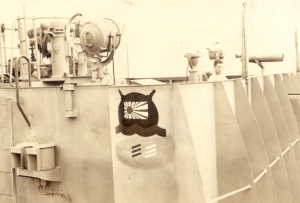

Poster on Bridge of USS Garland showing number of Japanese mines destroyed by the USS Garland

Explosion of a mine just aft of the Garland (Too close for comfort)